[ this is the script of the pre- and post-words I gave for a charity event Cabin-screening Friday night, down in Manitou Springs ]

wolf kisses and bear traps

The slasher. We can all make a list of our ten favorite, yes? Which of course we consider the ten best. So . . . that list starts where? Psycho, Peeping Tom? Bay of Blood? Maybe, maybe not. Definitely Black Christmas in seventy-four, anyway. And let’s not forget Texas Chain Saw Massacre from that same year, which gave us a mask, that all-important signature weapon. And you can’t ignore Jaws, either. Which, no, didn’t involve masks or signature weapons, unless teeth can count, but there was plenty of stalking the nearly naked, there was plenty of blood, plenty of looking through the killer’s eyes, and, for about the first time, plenty of what would become so important exactly four years later: theme music.

A lot of people say seventy-eight’s the real birth of the slasher, anyway. And maybe they’re right. That’s when it got codified, anyway. Which is to say that’s when John Carpenter gathered together and pioneered a set of suspense techniques and narrative developments and character types that, with people trying to clone Halloween’s success, got turned into conventions, into, as Randy would say in Scream nearly twenty years later, a list of rules, a formula. And that’s a formula we’ve all benefited from, isn’t it? Plug a killer into a group of licentious teens, and wait for the least licentious of them to not just survive, but overcome. When anybody’s talking ‘final girl,’ I mean, they’re talking Jamie Lee Curtis.

But, to get back to our list, our timeline: after Halloween, theaters across America were splashed with all the blood Tom Savini could budget: Friday the 13th, perhaps the most enduring slasher we’ve got, really. Because of the mask. Because of the machete. Because Jason never speaks, just stays this hulking mystery. And because teens just keep feeding themselves to his blade, like its an honor to have him kill you. But, in 1980, there was none of that yet. As Scream would remind us, it’s his mom who’s the killer in that one, yes? So how did it start one of the most popular franchises the box office has seen? It’s that ending, in the lake, with the canoe. You see it once and scream, clutch your armrests, and then you bring your friends back to watch them scream and clutch their armrests, and it snowballs into ten, eleven movies.

The next year, then, 1981, we got not only a cash-in sequel for Jason, but three serious entries in the slasher genre: The Burning, which was already messing with the ‘final girl’-formula; Just Before Dawn, which has maybe the most wonderfully violent final girl ever; and the Canadian import My Bloody Valentine, which got remade and 3D’d not long ago, here. But, as solid as these three were — and there were so many more besides — still, we’d have to wait until 1984 for the next big shake-up in the slasher. Cut to Wes Craven, following a news story about teens hiding coffee makers in their closet, because the boogeyman was going to get them in their dreams if they ever fell asleep.

Thus was born Freddy Krueger, in A Nightmare on Elm Street — starring Nancy Kerrigan, who’s special effects company you may know did the creatures for Cabin in the Woods, here. Which kind of automatically makes it legit, yes? But, Nightmare, man. When Wes Craven delivers, there’s nobody better. Here was a boogeyman who could infect all our dreams, a knife-fingered dude with not just a chip on his shoulder, but some actual wit. Which, sure, those wisecracks would maybe turn the series into something it was never meant to be, but still, when they worked, when, say, Freddy’s tongue comes through the phone, or when his torso is suddenly a television set, we screamed and laughed at the same time, didn’t we? And, really, Freddy’s where it all starts for me.

Thus was born Freddy Krueger, in A Nightmare on Elm Street — starring Nancy Kerrigan, who’s special effects company you may know did the creatures for Cabin in the Woods, here. Which kind of automatically makes it legit, yes? But, Nightmare, man. When Wes Craven delivers, there’s nobody better. Here was a boogeyman who could infect all our dreams, a knife-fingered dude with not just a chip on his shoulder, but some actual wit. Which, sure, those wisecracks would maybe turn the series into something it was never meant to be, but still, when they worked, when, say, Freddy’s tongue comes through the phone, or when his torso is suddenly a television set, we screamed and laughed at the same time, didn’t we? And, really, Freddy’s where it all starts for me.

I was twelve in 84, and by 85 Nightmare was on VHS, and we’d rent it every Friday night and watch it in my friend’s garage, at least until his dad would get drunk enough to put on his fedora and sneak outside, scratch his knife-fingers on the garage door. We’d run out the side, scream through the trees, and I don’t know if I’ve felt that again, quite. And, I say it starts with Freddy, but Michael’s there as well. In 78, sleeping on my grandmother’s living room floor, my aunt and uncle knocked on the door. They lived on the ten acres we had way out in the middle of nowhere West Texas. And they were wrapped in a blanket, and they asked if they could sleep on the floor, maybe. Why? I asked. Because they’d just seen Halloween, and couldn’t sleep in their trailer that night. And maybe not ever again. I distinctly remember stepping aside for them to pass, then looking out behind them, into the darkness. For this ‘Halloween.’ For Michael Myers.

But, talking Freddy, and screaming and laughing all at the same time (you could laugh and cry in a single sound) — that specific response, that shriek of delight, that’s the slasher’s special province, don’t you think? Physiologically, a laugh and a scream are the exact same response, up until the moment it comes out. The slasher lives and breathes in that instant of indecision, when you could respond either way. But, talking 84: anybody know what else was happening in slasher-land that year?

Our future was in his hands? James Cameron, yeah. Terminator. It’s science fiction, but it’s science fiction that’s built like a slasher. Just like Alien, yes? Terminator was also capitalizing on what Halloween had codified. And, sure, after 84, maybe the slasher did start to get a little too cumbersome, a little too formulaic. The golden age was drawing to a close, as all golden ages will. The slasher was becoming the kind of animal Carol Clover would dissect in her Men, Women, and Chainsaws, really. The sequels were getting obligatory and it was hard to tell the parodies from the supposed-to-be-serious stuff. There were a few gems in there, sure — Out of the Dark? Popcorn? — but by the early nineties, the closest we could get to a slasher anymore, his name was Hannibal, and he ate people, and he was in the same story as a very capable final girl. And he was good, don’t get me wrong, but the story they were in together was thriller, not horror. His victims weren’t teens out doing what they shouldn’t be doing. He was more like Ted Bundy in a mask, and with a taste for Beethoven.

Jason would never listen to Beethoven.

No, for true slashery goodness, the audience would have to wait until 1996. Kevin Williamson, Wes Craven, and Scream, a big little film that managed to both send up all the conventions we know and love and subscribe to them. It was a slasher about slashers, but it never went academic, quite, always opting for the jumpscare, the gag, the funny line instead.

No, for true slashery goodness, the audience would have to wait until 1996. Kevin Williamson, Wes Craven, and Scream, a big little film that managed to both send up all the conventions we know and love and subscribe to them. It was a slasher about slashers, but it never went academic, quite, always opting for the jumpscare, the gag, the funny line instead.

Scream made the slasher self-aware in a way it hadn’t been, I’m saying, and everything after was living in Scream’s world. Including, very much, Cabin in the Woods. But first there were all the Scream-clones. Of which I Know What You Did Last Summer probably got the most traction, in no small part thanks to Jennifer Love Hewitt being the new final girl. But Final Destination came alive as well, and started dismembering people at a pretty steady and inventive clip. And Jon Bon Jovi even got some of that bloody action, in Cry_Wolf. And let’s never-never forgot Jigsaw, lest we wake up to his voice:

For my money, the best of the post-Scream slashers is still All the Boys Love Mandy Lane (or, here), just because it subverts the conventions in a completely different way than Scream did. But you don’t have to subvert them at all anymore, if you don’t want. I mean. With Tucker and Dale vs Evil, all they had to do was flip the camera around, go from somebody else’s point-of-view. Or, flip that camera around once more and you’ve got Leslie Vernon, which I can’t really recommend enough.

For my money, the best of the post-Scream slashers is still All the Boys Love Mandy Lane (or, here), just because it subverts the conventions in a completely different way than Scream did. But you don’t have to subvert them at all anymore, if you don’t want. I mean. With Tucker and Dale vs Evil, all they had to do was flip the camera around, go from somebody else’s point-of-view. Or, flip that camera around once more and you’ve got Leslie Vernon, which I can’t really recommend enough.

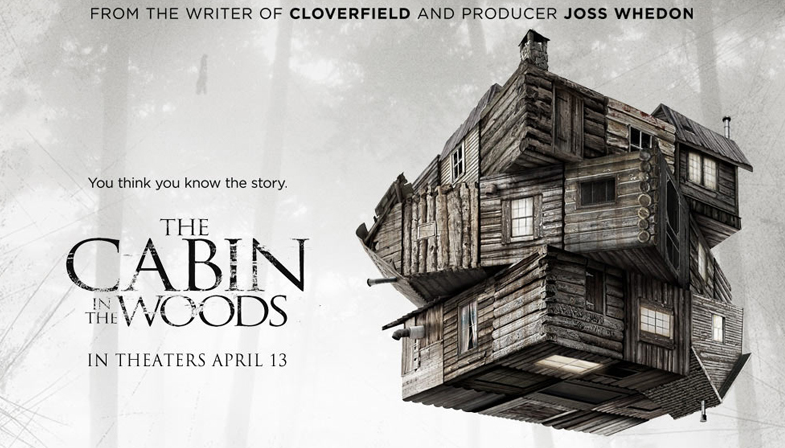

Which leaves us at Cabin in the Woods.

I would argue Cabin goes right up there on the board with all these. Really, it’s in the upper pantheon, even, the holy grail shelf, right along with Halloween, with Friday the 13th, with Nightmare on Elm Street and Scream. And, while it feels like a bookend to this whole slasher thing, in that you have to ask How can it escalate any farther? — don’t worry. The slasher’s never really over. Even after it’s dead, look, you can always see its finger twitching, if you watch closely enough.

And, while I don’t want to spoil Cabin the Woods for you — I’ll be speaking more about it after the movie, this is all just set-up, pep-rally — let me say just two names: Drew Goddard, of Cloverfield, of Lost, of Alias, of Buffy, and Joss Whedon, he who gave us Buffy, and Firefly, and Angel, and The Avengers, and — did I say Firefly already? It bears repeating. These two guys, Drew Goddard directing, Joss Whedon producing, the two of them writing together, they bring not only an awareness of the genre, but a love of the genre. And that’s so, so important.

With Cabin, you never even once feel they’re trying to cash in, like they did some marketing research, figured they could rake a few box office receipts in with a movie like this. No, they’re doing this from a true and abiding love of the slasher, I think. They’re doing it because they care about the slasher, and want to prop it back up again, give it new legs for a new audience.

They each claim that Evil Dead is their main reason for doing Cabin in the Woods. But then they’ll claim Hellraiser as well. And all the rest besides. Cabin is exhaustive in its homage, really. No, it’s wonderful in its homage. But it never even for a moment forgets what it’s been promising to deliver all along: blood. Buckets and buckets of blood. The amount of blood they were using towards the end, it’s up in Peter Jackson territory, I mean. And the monsters, man. The monsters. But you’re ready to see this, I think. Just one more thing.

They each claim that Evil Dead is their main reason for doing Cabin in the Woods. But then they’ll claim Hellraiser as well. And all the rest besides. Cabin is exhaustive in its homage, really. No, it’s wonderful in its homage. But it never even for a moment forgets what it’s been promising to deliver all along: blood. Buckets and buckets of blood. The amount of blood they were using towards the end, it’s up in Peter Jackson territory, I mean. And the monsters, man. The monsters. But you’re ready to see this, I think. Just one more thing.

When I first saw Cabin in the Woods, it was up in Boulder, at some early sneak screening, with t-shirts and Goddard and Amy Acker and others there. And all the posters as I was walking in, they were saying that I thought I knew the story. And, I mean, come on, I’ve been there since Freddy, I’ve gone back to Hitchcock and Agatha Christie and Robert Mitchum, I’ve peeled through the indies and microbudgets and film festival entries (Madison County and the Cold Prey series stand out), I’ve read every book ever done on the slasher (in one, too), watched all the documentaries, I’ve taught the slasher, and I’ve even written a couple. If it’s slasher, chances are I’ve seen it, or read it, or read about it. So, yeah, I was pretty sure that poster wasn’t for me, that I already had that Rubik’s Cube of a cabin solved in my head. I thought I did know this story.

I was wrong. And I’ve never been so happy to be so wrong.

So, laugh, scream, and don’t decide which until the last possible instant. Hope you like this as much as I do,

{ insert movie here, with trivia intermission }

{ so, now that the movie's over . . . }

so much heart

The best stories make you reconceptualize everything you thought you knew. So, Randy’s formula from Scream, that’s supposed to account for the slasher in all its goriness — what Cabin in the Woods has done here is, first, agree with it a hundred percent, support it, validate it, but then it shows us that when the crew splits up like they always do, it’s because the story department’s told the chem department to make it so. And when they have sex at the most unlikely times — it’s pheromones and mood-lighting and temperature control. The characters don’t ‘deserve it’ like we’ve always thought.

The best stories make you reconceptualize everything you thought you knew. So, Randy’s formula from Scream, that’s supposed to account for the slasher in all its goriness — what Cabin in the Woods has done here is, first, agree with it a hundred percent, support it, validate it, but then it shows us that when the crew splits up like they always do, it’s because the story department’s told the chem department to make it so. And when they have sex at the most unlikely times — it’s pheromones and mood-lighting and temperature control. The characters don’t ‘deserve it’ like we’ve always thought.

Watch Cabin enough times, and you start to see Goddard and Whedon were checking off a list: sex, drugs, nudity, isolation, the country, a certain set of stock characters. However, where a lot of stories make fun of those tropes — like I was saying, Cabin, it adores those tropes. It’s a defense of those tropes. With every story, at some point you have to ask what your takeaway is. What you’re getting for your buck, here. With Cabin in the Woods, I think what you’re getting is a re-legitimizing of every cheesy, poorly-produced, poorly-conceived slasher that’s stolen two hours of our lives and ninety-nine of our cents. If you believe in Cabin in the Woods, then you understand that, without those slasher stories, then the world would have fallen to the elder gods long ago. Those stories have been our last defense since the dawn of man — since our long night was finally over. Which, what this means, it’s that these extraordinarily stock characters, by sacrificing themselves, they’re heroes, they’re keeping the world together. That Nicholson’s line from A Few Good Men, about how we don’t want to know the things the military has to do to let us sleep safe in our beds? We can’t handle the truth? Cabin in the Woods is that truth.

And you’ve got to appreciate the writing, don’t you? Remember the ‘Le royale with cheese’-water-cooler banter that begins this story? It’s Hadley, talking about how his wife is babylocking the house up, about how he can’t get a beer without it taking twenty minutes and two crushed fingers. The whole movie’s kind of packed into that, right there. In Cabin, you’ve got a world of doors that will be wonderfully unlocked by the end of the story, and you’ve got a terrible, unknowable infant about to be born, a huge hungry, irrational baby that’s about to change everything we thought we knew about living.

And, irony, man. Without irony, stories have no resonance. And Cabin in the Woods . . . this is Joss Whedon and Drew Goddard, after all. There’s irony to go around. The most obvious is our final girl, Dana, which is of course an appropriately gender-neutral name. Like Ripley. Like Sidney. And, as she should be, she’s considered the ‘virginal’ one by the group, she wants to take actual textbooks on this crazy weekend, and she’s got an issue she needs a horror story to solve for her: an affair-gone-bad with a professor. So, she’s built right, is exactly the kind of final girl every slasher movie needs. But the irony, it’s that she’s finally built too well, isn’t she? In all the long history of final girls, she’s the only one to ever step through that fourth wall, into the production studio of the Truman Show, into the scream factory of Monsters, Inc. No, let me say it different: she’s the only one to ever fight her way through. The only one to ever survive that long. All the lesser final girls, they stayed topside, didn’t they? But, this time out, in this slasher, the story department or whoever’s in charge of picking sacrificial victims, they picked a final girl who’s a little too capable. Instead of fighting the puppets like she’s supposed to, she goes for what Marty calls the puppetmasters. Worse—or, irony on top of irony? — after she’s broken down all the tropes and conventions, shown that they don’t apply to her, that they’re not in play here in the same way, what does she do? She smokes a joint.

Were Jason in the area, she’d have a machete whistling at her neck already.

This is another level of slasher, though. Instead of that machete, there’s a giant hand coming for her. Cabin in the Woods is both thumbing its nose at Jason and Freddy, at Michael and Leatherface, at Ghostface and Chucky, and it’s pulling them all close.

It’s those kinds of tensions that create the best vibrations, the most harmony. It’s these kinds of stories that change a genre.

And the telescoping bong, it’s just the slide whistle for us there.

And, Cabin, sure, it’s drawing on every slasher known to man, but, I mean, either Whedon or Goddard, they maybe know their Russian formalism, too. I’m thinking this one dude Vladimir Propp, who did The Morphology of the Folktale back forever and a half ago. What he did with folk tales is collect them all, and kind of reduce them to algebra. So, if a story starts out with a princess in X situation, and monster Y suddenly comes on scene in manner Z, then developments A, B, and C are now inevitable. Everything’s built into how a thing begins.

I’m talking about the cellar. I’m talking about Don’t Read the Latin.

That Evil Dead cellar, man, it would have been Vladimir Propp’s wet dream.

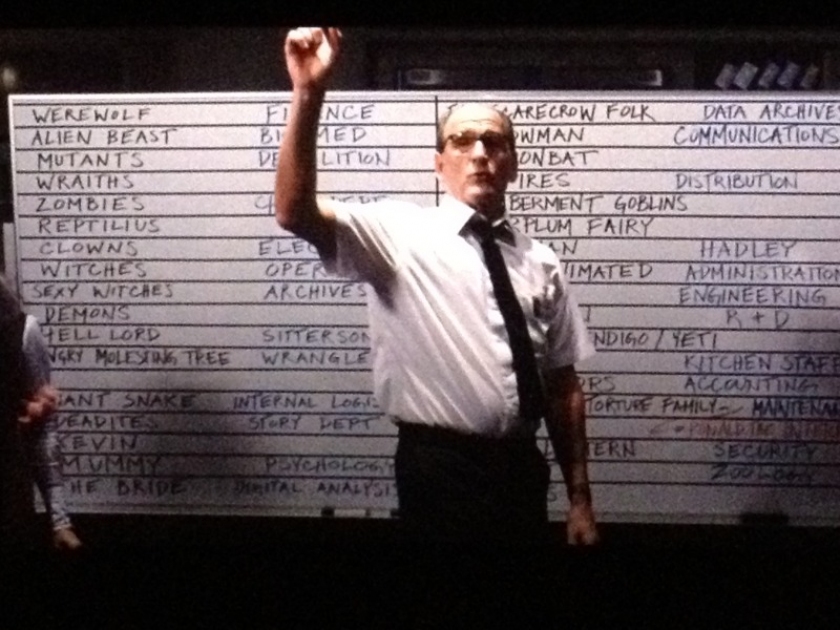

And the magic of it is that that’s where the story branches. Sure, we go the ‘Zombie Redneck Torture Family’-way with those dependable Buckners. This time. But once we realize what’s happening, then that whiteboard in the control room, it comes alive. With mermen. With vampires. With angry molesting trees. With unicorns. With ‘Kevin.’ And, watching that second act unfold, all those other stories are running simultaneously now.

This is where Cabin the Woods gets its depth from: narrative, not metaphor.

This is how you tell a story.

Also, talking storytelling, talking writing a story: how convenient must it be to, instead of dealing with foreplay and steamy eyes and clever dialogue, just to have somebody push a button for pheromones, turn the moonlight up, crank the heat? What this allows a story to do is cross a lot more terrain, because it doesn’t have to slog through the boring parts.

And, as you’ve just seen, with Cabin, there are no boring parts. Even that ‘Le royale’-title sequence they rigged specifically to make us think we were in the wrong movie, right at the exact moment we’re looking around to see who else might be looking around, they splash that title hard and red and loud on the screen, jolting us into their story:

It’s the opposite of boring, I’d say.

Also, note how the three acts of most slashers, Whedon and Goddard here, they’ve compressed them down to two: the final girl’s going toe-to-toe with the slasher, doing that very important life or death fight where she realizes what she’s really made of, at the end of the second act. On the dock? Playing on the three screens in the control room, behind the “tequila is my lady”-party?

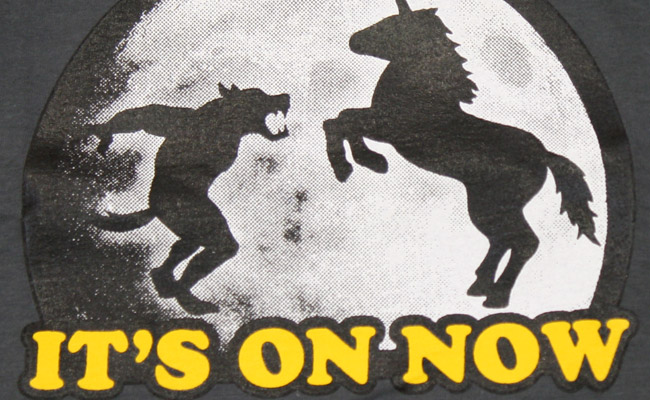

What that leaves Cabin free to do is throw us into completely new territory, a third act like the slasher hasn’t really seen. They called the set for those elevators the ‘white’ set. Because it so obviously wasn’t. What that white set is, what everything is after Dana hits that ‘purge’ button, it’s a dramatization of that t-shirt I showed you before the movie: It’s on now.

And, once we’ve seen the spotlight deaths of all our control-room administrators — and wonderful deaths they are — and a certain famous actress walks up those stairs . . . were you expecting Ripley? She was perfecter than perfect, yes? She was like the final escalation, when it would seem that the story really has to have been out of escalations a few minutes ago, when the unicorn stabbed that brown whitecoat.

This is new territory, though. Back in the golden age of the slasher, there was constant competition, to out-do the slasher from last month.

With Sigourney Weaver, Cabin pretty much wins that contest.

And, yeah, having Jamie Lee Curtis walk up those stairs, that would have had us crying in the aisles, definitely. But I think what Whedon and Goddard wanted at that moment was to plant us deeper in our seats. To make us sit there, hanging on their Director’s every word as the world balanced on Dana’s decision.

And, yeah, having Jamie Lee Curtis walk up those stairs, that would have had us crying in the aisles, definitely. But I think what Whedon and Goddard wanted at that moment was to plant us deeper in our seats. To make us sit there, hanging on their Director’s every word as the world balanced on Dana’s decision.

At which point the final girl becomes the philosopher, and that’s not one of the five archetypes.

What she decides, it’s what she has to. It’s Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery.” It’s Ursula K. LeGuin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” It’s the end of Bret Eason Ellis’ Less Than Zero.

Do we really deserve to live, if this is the cost? If, as in “The Lottery,” we have to stone one citizen so that all the others can go on living their happy lives, then doesn’t that mess ‘happy’ up just a little?

For Dana it does, yes.

Her job in this ritual, a ritual we’re just now becoming aware we’ve been important participants in all along — in a sense, we’re the elder gods, who must be appeased — her job in this ritual all along, it’s been to sacrifice herself and her friends. But then, when she could ‘win,’ when she could live, she elects to make an even bigger sacrifice. For all of us.

She’s not trying to save our lives. She’s trying to save our souls.

And, with what?

With horror. That’s got to be the final takeaway of Cabin in the Woods. It’s nothing political, like don’t stockpile weapons of mass destruction — cenobites and deadites and dragonbats — because they always get away. It’s that horror has a purpose. With Cabin, Whedon and Goddard are like Dee Snyder of Twisted Sister in the eighties, Mr. Smith’ing his way to DC to stand in front of all our representatives, insist that there’s nothing wrong with rock and roll.

With horror. That’s got to be the final takeaway of Cabin in the Woods. It’s nothing political, like don’t stockpile weapons of mass destruction — cenobites and deadites and dragonbats — because they always get away. It’s that horror has a purpose. With Cabin, Whedon and Goddard are like Dee Snyder of Twisted Sister in the eighties, Mr. Smith’ing his way to DC to stand in front of all our representatives, insist that there’s nothing wrong with rock and roll.

There’s nothing wrong with horror, either. And there never has been. Sure, it’s got its excesses, and it traffics in transgressions, and it doesn’t always hold itself to the highest standards. But, as Cabin in the Woods illustrates so bloodily, it’s what keeps the world alive.

Unless the real horror here, it’s that the people keeping us safe in our beds at night, the people keeping the monsters at bay, they wear ties with short-sleeved shirts, and they have office betting pools, and, like Dr. Doofenschmirtz, they build their own self-destruct buttons, and paint them red, say don’t push this, please.

On them the world depends.

If that’s not horror, I don’t know what is.

Thank you,

{ also, here's my original review of Cabin, before I knew who Kevin was }

{ click Sitterson to go to the official Cabin in the Woods site }

is the NYT bestselling author of 30 or so books, +350 stories, some comic books, and all this stuff here. He lives in Boulder, Colorado, and has a few broken-down old trucks, one PhD, and way too many boots. More

is the NYT bestselling author of 30 or so books, +350 stories, some comic books, and all this stuff here. He lives in Boulder, Colorado, and has a few broken-down old trucks, one PhD, and way too many boots. More